Introduction

The seaborne assault and landing phases of the Allied invasion of Normandy in

1944 was perhaps the largest, most intricate and meticulously planned naval

endeavour in WWII. Paramount to its success was the absolute necessity for a

vast amount of requisite detailed work in its conception, planning and execution

to maximise success and minimise intent to the enemy. Nothing could be

overlooked in the planning of this ambitious operation if the landing forces

were to gain a successful bridgehead and lodgement, with the necessary elements

of surprise and speed, upon the five designated beach areas and beyond. It seems

incredible today to realise that approximately seven thousand individual vessels

were to be involved in the subsequent period to the end of July 1944, including

warships, troop landing craft, transport, supply and support ships.

To the minesweepers and their attendant consorts was to fall the responsibility

of leading the assault forces to the Normandy beaches. Contingent upon their

effectiveness and timely efficiency in clearing the German mine barrier

protecting the area, there lay the potential to cross that finely dividing line

between success, or otherwise, for the opening day of this amphibious opposed

invasion to establish the second front. The interested researcher can find much

of relevance regarding Operation Neptune in official Admiralty archives, naval

and war museums and indeed one’s local public library. Conspicuous by their

absence are accounts of minesweeping operations and movement logs of individual

minesweepers or their flotillas. Yet the minesweeping workloads during the

months of June and July 1944 were absolutely vital to the success of the beach

landings in terms of men and materiel. That relatively few warships, transport

or landing craft were seriously damaged or lost due to conventional mines is

fitting testament to the organisation and work of the plucky crews of these

valiant, but unheralded little ships, who assured that approach routes,

bombarding ship and landing craft anchorages were as free as possible of mines.

Fig (i) courtesy of Algerine Association website

(see References)

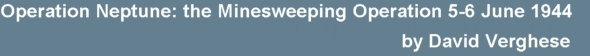

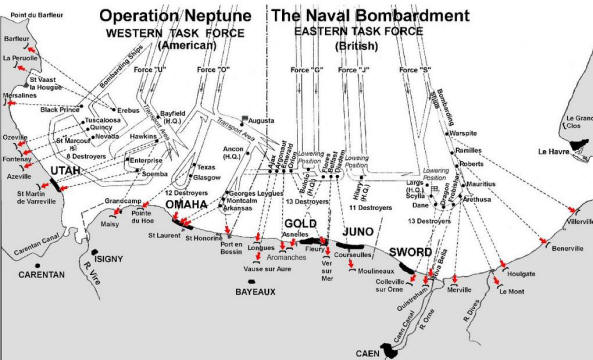

By well into 1944 minefields were known to have been laid in depth south of latitude 50 degrees N to within ten miles of the French coastline; these fields stretched from offshore Boulogne to the Seine Bay (see map (i)). South of the mined area existed a clear channel used by the Kriegsmarine. The Allied naval planners intended to utilise this channel as the lowering positions for the landing ships to bring in the infantry troops. Ground mines were assumed to be laid between this channel and the beach areas – and these would need to be swiftly cleared just prior to the landings, and opportunity denied to the enemy to lay further mines.

The sea mining of the waters chosen for Operation Neptune was potentially both a lethal and most disruptive weapon available for the German forces. The Neptune routing plan devised involved directing amphibious forces from a large number of ports in southern Britain into Area ‘Z’ (see map (ii)) before turning southwards through the ‘Spout’ and into what would be initially ten channels leading to the lowering positions in the beach assault areas.

Map (ii)) courtesy of Gordon Smith, and adapted from Stephen Roskill’s

War at Sea

Planning

The Minesweeping Operational Plan, drawn directly up by Admiral Bertram Ramsey and the Task Force Commanders (Eastern: Rear Adm. Sir Philip Vian RN; Western: Rear Adm. Alan G. Kirk USN), was essentially in the following four overall parts:

(i) In respect of each of the five beach Assault Forces (designated U, O, G, J and S), two channels would be cleared S.SE. through the mine barrier for the first wave of amphibious infantry on what would be termed D-Day. One assault channel would be for 12 knot convoys and one for slower 5 knot convoys. These channels were to be numbered 1-10 from west to east. A Fleet Minesweeping Flotilla (MSF) of nine ships would be allocated to each channel to sweep well ahead of the invasion vessels. It was of paramount importance to conceal from the enemy the time and place, and indeed intent, of the landings by the forces following up behind.

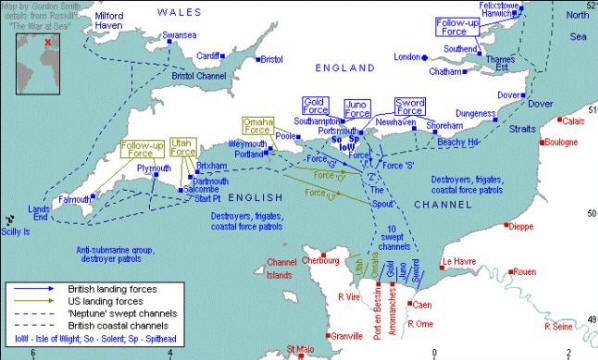

(ii) Inshore of the coastal channel a Minesweeping Flotilla would precede the movement of the Bombarding Forces of warships to clear the presence of any mines right up to the anchorages of these ships. (the final D-Day positions of the bombarding ships in relation to the five paired channels and the beach areas is shown in map (iii) courtesy of combined ops website). These Bombarding Forces (designated A, C, K, E and D) would target enemy fortifications, gun battery emplacements and reinforcing armour that might be brought up from their reserve points to pose an immediate threat to the LSI(L) craft disgorging infantry onto the five beach areas. There were ground mines, acoustic and magnetic, thought to populate the inshore areas, and the pathway of the bombarding ships had to be commenced as soon as the channels were initially cleared.

Map (iii) The Operation Neptune

Bombarding Forces on June 6 1944

(iii) When the above two tasks were accomplished, planned to be by 0500, the next phase would be to widen the mine-freed approach channels to form a broad area ( known as the ‘SPOUT’) to allow passage of supply and equipment vessels carrying armoured fighting vehicles.

(iv) Constant re-clearing activities were to be maintained in order to nullify mines dropped by parachute from enemy planes or laid from E-boats. To counteract Allied success the enemy did, to some limited extent only, engage on this re-laying with all types of mine including the relatively new oyster mine – these latter were designed to actuate by changes in water pressure as a ship passed in its immediate vicinity. Allied vessels were obliged to slow their speed to a point where pressure generated would be too low to trigger actuation.

Thus one can begin to appreciate the inherent potential danger facing the minesweepers and their crews if the enemy, realising the intent and efficacy of the mine clearing operation, responded with air and fast E-boat attack in the early dawn light. Kriegsmarine Group West actually failed (much to the frustration of Vice Admiral F. Ruge, Rommel’s Naval Advisor) to reinforce the mine barrier with new mines and to lay ground mines with delay action fuses off the beaches. This would have made the task of the minesweeping flotillas much more difficult given the time constraints of the overall operational requirements. They were required to keep station and make difficult turns in changing tides as an operational flotilla in the dark and with rough sea. There is no doubt that the minesweeping flotillas would have to take great risks as an acceptable hazard – if engaged they were required to keep to their sweeping courses as allocated. Incredibly, several of MSFs encountered no enemy reaction as they reached the southern end of their respective channels, allowing them to turn parallel to the beaches sweeping for some distance, before heading northwards to sweep ahead of the Bombarding Forces or to widen the channels.

Order of Battle of the MS Flotillas

In total, about 350 vessels of many types took part in the mine clearing operation of June 5-6. Within each Channel-tasked MSF the typically eight Fleet Minesweepers used (a further was held as reserve for each channel) carried not only gear in abundance to deal with the various types of mines they might encounter but also equipment to deal with the anti-sweeping devices built into the mines. The Fleet Minesweepers were augmented by usually four Danlayers and a small number of Harbour Defence Motor Launches. The latter vessels shallow swept ahead of the Fleet Minesweepers in a protective role. There were other classes of minesweepers as outlined in the table below, and the final type of vessels were the Oropesa “twin Longitudinal line” (or LL) Trawlers of the RN Groups 131, 139, 159 and 181. Two were allocated for each channel flotilla, their equipment being specialised for the sweeping of magnetic mines.

It is worth noting the very precise work of the Danlayers in each Flotilla. Of the four vessels, and occasionally a minesweeper in reserve was tasked for this role, one pair was to follow the Flotilla Leader’s sweep to mark one side of the allocated channel with lighted dan buoys, the other pair would follow the rear minesweeper to mark the opposite side of the channel, each channel varying from 400-1200 yards width. The minesweepers swept in what is termed ‘G’ formation of roughly quarter line, each ship being covered by the outside portion of her next ahead’s sweep wire. The first dan buoy displayed particular flags and a characteristic light to distinguish it clearly from the dan buoys of the neighbouring channels. The next three buoys were laid near the centre line of the channel and then the channel was marked at one-mile intervals, each side of the channel having the same lights and flag, but different to the light and flags of the other side. The reserve pair of danlayers filled in the gaps where buoy lights were broken. By late June 7 Trinity House would replace the dan buoys with ocean light buoys. In the opening phase of Operation Neptune covering June 5-6, the 350 (approx) total minesweeping force carried out tasks as follows:

|

Flotilla 1st 4th 6th 7th 7th USM Squadron 9th 14th 15th 16th 18th 31st RCN 32nd RCN 40th |

Class or Type Halcyon Aberdare (Hunts) Algerine Algerine AM(US) Bangor Bangor Bangor Bangor Algerine Bangor Bangor Catherine (BAMS) |

Role covered Swept Ch. 9 ahead of Force S Swept Ch. 4 ahead of Force O Swept Ch. 5 Swept Ch. 8 Swept ahead of USS Nevada, Tuscaloosa and Quincy Swept Ch. 7 ahead of Force J Swept Ch. 2 ahead of Force U Swept Ch. 10 Swept Ch. 1 ahead of Force U Swept Ch. 6 ahead of Force G Swept Ch. 3 Used as required Followed the 15th MSF down Channel 10, then proceeded to within 2 miles of beach area, then met and swept ahead of Bombarding Force D which was protecting theForce S assault craft. |

The British YMS, YMS (US) and British

Motor Minesweepers below were given the role to sweep the inshore areas,

especially the boat lanes between the transport areas and the beaches, and

subsequently the artificial Mulberry harbours after the assault phase. They were

equipped with light sweeping gear especially designed for sweeping magnetic and

acoustic influence mines in shallow waters. A small number of LCTs were also

similarly equipped.

British Yard Mine Sweeping (BYMS) Flotillas – 150th, 159th,

165th, 167th

YMS Flotillas (US) – Y1 and Y2

Motor Mine Sweeping (MMS) Flotillas – 101st, 102nd, 104th,

115th, 132nd, 143rd, 205th

By 0330 the ten channels had been swept by the Fleet Minesweeping Flotillas and

shortly after the inshore areas parallel to the landing beaches had been swept

by the BYMS, YMS and MMS ships. The Assault Flotillas were well into their

passage to the Gold, Juno, Sword, Utah and Omaha Beaches to arrive by H-hour,

and the bombarding squadrons of battleships, cruisers, monitors and destroyers

were now ready to let loose the most concentrated firepower of naval ordnance

ever experienced in the history of sea warfare against a land-based foe.

The minesweeping flotillas, having been given the honour of leading the way for

the Allied Assault Forces, now moved northwards, either widening the channels or

withdrawing to holding areas in what was to become, over the next few days, the

‘Trout Line’. This was a defence barrier set up around the Normandy anchorage to

protect the ships from the multiple threats of E-boats, R-boats, human 'Neger'

torpedoes and Linsen explosive motor boats. The ‘Trout Line’ itself was composed

of LC(Guns), LC(Flak) and LC(Supply) set up in a continuous double line one

cable apart. The minesweepers slotted in at 5-cables (half mile) intervals six

miles seaward on each side and parallel to the beaches. Sword Beach, on the

eastern flank, was particular vulnerable to attack from the Le Havre area and

enemy submarines were always a potential risk apart from the offensive threats

above".

Coastal Forces Control Frigates patrolled just outside the line sometimes

augmented by destroyers thereby adding to defence in depth. Ships' speeds had to

be tempered, knowing the potential to actuate the newish oyster mines.

Those 350 or so ships, from the Flotilla leaders to the Fairmile B MLs, had

engaged in the most meticulously planned and well executed minesweeping

operation ever undertaken and all had survived by the end of D-Day on June 6.

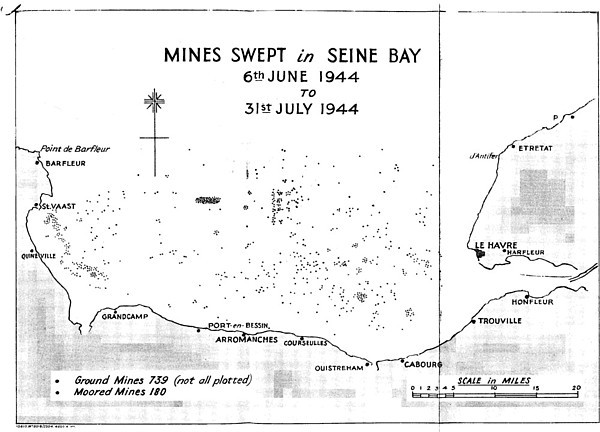

Mines swept in Seine Bay 6 June to 31

July 1944 courtesy of Michael Friend

This narrative will close with a fitting tribute paid to all those involved, by the Naval Commander of the Western Task Force, Rear Admiral Alan Kirk USN. (ADM 234/366 p. 49).

"It can be said without fear of contradiction that minesweeping was the keystone in the arch of this operation. All of the waters were suitable for mining, and plans of unprecedented complexity were required. The performance of the minesweepers can only be described as magnificent."

___________________________________________________________________

These are the type of men the Vernon Monument will be celebrating and one of the reasons I am so passionate to see it erected. To read about the activities of members of the Landing Craft Obstacle Clearance Units (LCOCUs), the first men ashore on D-Day, see Operation Neptune: Frogmen - The First Men Ashore on D-Day by Rob Hoole in the website's Dit Box.

References: